A Scene Out of a Documentary — But Very Real

It began like any other morning in the tropical heart of the Congo Basin. Market vendors laid out baskets of bananas, mangoes, and cassava under woven canopies as the mist lifted from the forest. The sound of chatter filled the air — until someone shouted, “They’re back!”

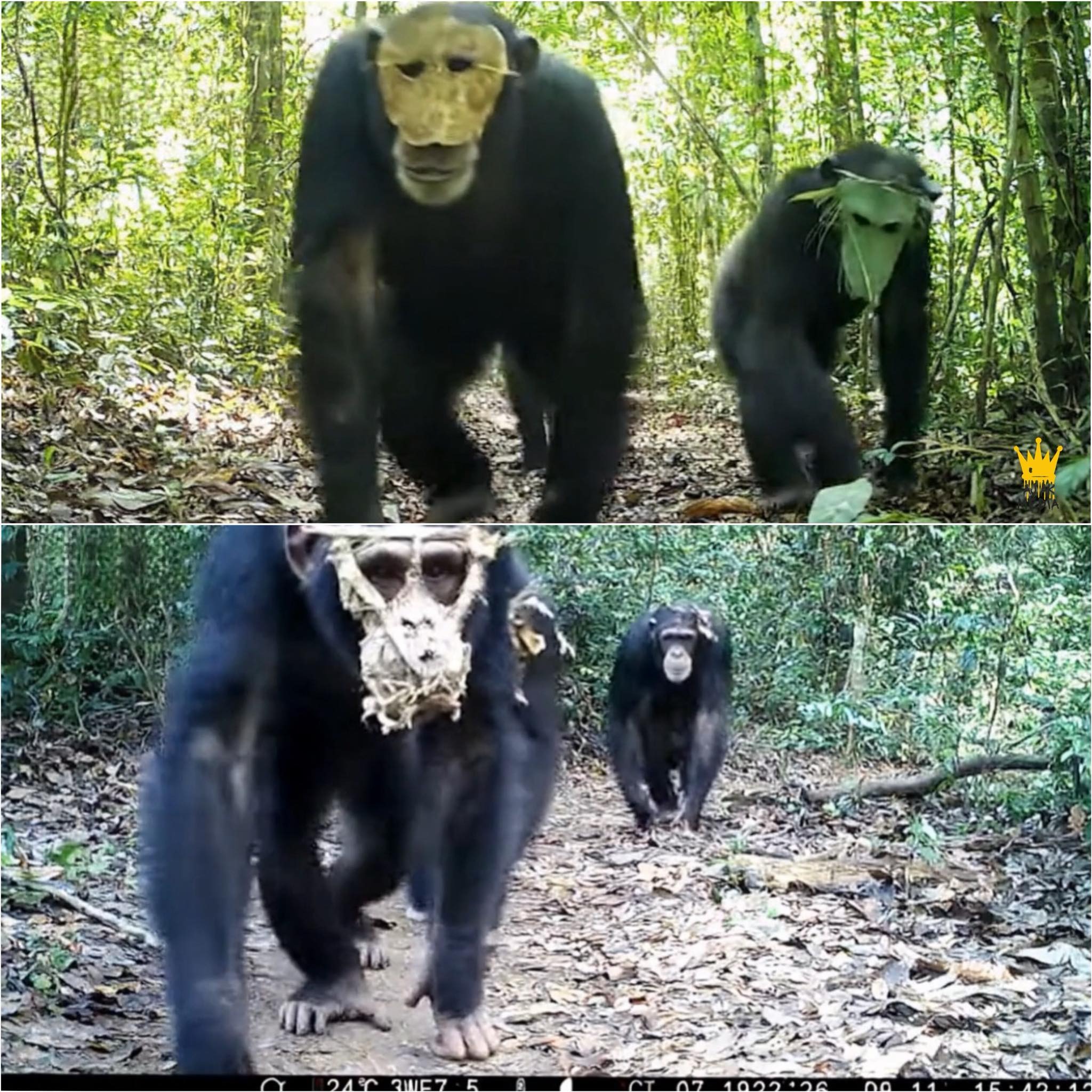

Out from the trees came a group of chimpanzees, moving quickly, quietly, and — astonishingly — wearing masks.

Witnesses described the masks as crude but deliberate: leaves tied together with twigs, pieces of bark draped over faces, and even scraps of discarded cloth. Within moments, the chimps grabbed fruit from the stands and vanished back into the greenery.

When the startled vendors later reviewed phone footage, they realized what had just happened wasn’t an ordinary animal raid — it was an extraordinary display of adaptation.

The Story Behind the “Masked Chimps”

Local authorities in the northern Congo confirmed that incidents of chimpanzees entering markets had been reported before, usually involving single animals stealing fruit or leftover food. But last month, when one chimp was captured and relocated after repeated raids, something seemed to change.

Soon after, entire groups began approaching markets — but this time, they acted differently.

“They were organized,” said a market vendor from Mbomo village. “They waited until people were distracted. They covered their faces, took what they needed, and disappeared.”

Though some residents initially doubted the reports, multiple videos surfaced showing small chimp groups — typically four to six individuals — wearing face coverings of leaves or cloth while carrying out coordinated raids.

Researchers investigating the footage say the behavior appears to be a learned adaptation — a response to human action, showing a sophisticated understanding of cause and effect.

A Landmark Moment in Primate Research

Primate experts have called the footage one of the most fascinating examples of collective learning and problem-solving seen in wild chimpanzees.

Dr. Samuel Biyombo, a behavioral ecologist with the Congo Primate Research Institute, explains:

“These chimps appear to have modified their behavior after observing one of their own being captured. This suggests not only memory and emotional response but also a group-level strategy to avoid future risk.”

He adds that while chimpanzees have long been known to use tools — from sticks to extract termites to stones for cracking nuts — the use of facial coverings for concealment represents a rare level of adaptive creativity.

Scientists caution against anthropomorphism (assigning human motives to animal behavior), but acknowledge that such actions indicate a deep awareness of cause, consequence, and collaboration.

How Chimps Learn — And Teach Each Other

Chimpanzees live in tight social groups where imitation and teaching play vital roles. Studies from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology show that chimps pass knowledge through generations — including techniques for hunting, gathering, and tool use.

In this case, researchers believe one or two high-ranking individuals may have first experimented with masking behavior, which others then copied. This process, known as cultural transmission, is central to how non-human primates evolve behavior in response to new challenges.

“Chimpanzees are not just reacting instinctively,” says Dr. Biyombo. “They’re observing, remembering, and sharing strategies — a hallmark of culture.”

What the Footage Reveals

Analyzing the videos, researchers noticed consistent behaviors:

-

The chimps often approach markets in early morning or twilight hours when fewer people are around.

-

One or two individuals act as lookouts, while others gather food.

-

Some even appear to adjust their coverings when humans draw near.

These observations suggest planning, communication, and awareness of being watched — complex traits once thought to be uniquely human.

Wildlife experts are careful to note that while the masks may not truly “disguise” the chimps from human recognition, the act itself implies symbolic thinking — associating covering the face with safety or concealment.

Such thinking marks an advanced cognitive leap, one that challenges how scientists define intelligence across species.

The Cultural Side: How Communities See the Chimps

In many parts of Central Africa, chimpanzees occupy a unique place in folklore. They are seen not merely as animals but as forest guardians — beings that mirror human behavior in surprising ways.

Elders in Mbomo village recalled stories of “nkosi ya ndima,” the forest brothers, who imitate humans to survive. To them, the masked chimps were not villains but reflections of adaptation — an echo of how nature responds when pushed too close to human boundaries.

Local residents have since adjusted their market schedules and begun setting aside food offerings outside the forest, hoping to reduce raids. What began as shock has slowly transformed into respect — and even a sense of shared coexistence.

The Science of Adaptation: Why Chimps Outsmart Challenges

From Tanzania’s Gombe Stream to Uganda’s Kibale Forest, chimpanzees have repeatedly demonstrated remarkable ingenuity. They fashion spears to hunt smaller animals, build sponge-like tools to collect water, and coordinate group hunts with precision.

The Congo case adds a new dimension: socially coordinated deception — or at least the semblance of it.

“This behavior reflects a flexible intelligence shaped by environmental and social pressures,” says Dr. Lila Rosen, a cognitive scientist from the University of Cambridge. “It shows that when humans alter their surroundings, animals adapt — sometimes in ways that mirror our own strategies.”

According to Dr. Rosen, such events remind us that intelligence is not a single ladder with humans at the top, but a spectrum where many species display brilliance suited to their world.

Understanding Intelligence Beyond Humanity

For decades, scientists defined intelligence primarily through human-like reasoning: language, technology, and self-awareness. Yet, modern research has broadened that view.

Chimpanzees use over 60 distinct gestures to communicate. They mourn losses, reconcile after conflicts, and plan actions days in advance. When faced with obstacles — such as human deterrents — they innovate.

The “mask phenomenon,” while still under study, may become a cornerstone example of environmental learning — proof that when faced with human challenges, other species don’t merely retreat; they think.

In evolutionary terms, such adaptability is what ensures survival in changing landscapes. The chimpanzees of the Congo are doing what nature designed all species to do: observe, adapt, and endure.

Ethical Questions and Conservation Implications

The masked chimp incidents have sparked renewed conversations about the ethics of human-wildlife interactions. As deforestation and expanding markets encroach on forest habitats, encounters between humans and chimpanzees become increasingly common.

Experts emphasize that these animals are not intruders but displaced residents seeking food in shrinking ecosystems.

Conservation organizations in the region, including Wild Congo Alliance and EcoHabitat Network, are using this case to raise awareness about habitat protection and sustainable coexistence. They hope to establish buffer zones and wildlife corridors that reduce conflict while preserving biodiversity.

The Role of Curiosity in Discovery

The world’s fascination with the “masked chimps” story reveals as much about humans as it does about primates. We are drawn to behaviors that blur the boundary between instinct and intellect, between nature and ourselves.

When we see another species adapting creatively, it challenges our assumptions — reminding us that intelligence is a shared legacy, not an exclusive club.

Curiosity drives us to observe, document, and understand these moments. It also compels us to look inward, asking what it truly means to be intelligent — to learn, to cooperate, and to adapt with empathy.

From Folklore to Science: The Timeless Appeal of Animal Stories

Long before modern research, human cultures told stories about animals that could think, plan, and even disguise themselves. From trickster tales in African mythology to moral fables in ancient Asia, animals have often been mirrors reflecting human nature.

Today’s scientific discoveries don’t replace those stories — they deepen them. Seeing chimps cover their faces with leaves isn’t just a curious event; it’s a continuation of an age-old dialogue between humans and the creatures that share our planet.

In blending myth and evidence, we find not contradiction, but harmony — a reminder that both imagination and science seek the same truth: understanding life’s complexity.

Reflection: What the Masked Chimps Teach Us About Ourselves

The image of a chimpanzee wearing a mask in the middle of a bustling market may seem surreal, almost cinematic. Yet beneath that image lies something profound — a lesson about adaptability, awareness, and the thin line that separates instinct from understanding.

These chimps, acting on memory and observation, remind us that intelligence is everywhere — not confined to humans, but expressed uniquely across the living world.

Human curiosity, the same force that led researchers to study this event, is also what drives empathy. When we see others — human or animal — adapting to survive, we recognize a reflection of our own journey.

In the forests of the Congo, a group of chimpanzees has shown that learning, cooperation, and creativity are not just human traits — they are universal languages of life.

And perhaps that is the real story here: that in a rapidly changing world, the greatest sign of intelligence is not domination, but the shared ability to adapt — thoughtfully, compassionately, and together.

Sources

-

Congo Primate Research Institute – Field Notes on Behavioral Adaptation (2025)

-

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology – Studies on Primate Culture and Learning

-

National Geographic – “Chimpanzee Behavior and Intelligence in the Wild”

-

BBC Earth – “The Hidden Minds of Primates”

-

University of Cambridge Primate Cognition Unit – Expert Commentary on Social Learning

Leave a Reply